Where Do We Go for Innovation in Art…

The work in public museums is mostly decided on getting the highest number of visitors, which generally rules out anything too risqué. Yet, the history of modern art is built on innovations that challenge, divide and even offend. Recalibration is what innovation is built on, but it is not always best suited to attract audiences. Is contemporary art doomed to be entertainment, or are there still places where the risk-taking takes place? The answer lies in smaller enclaves such as galleries set up and run by artists themselves, where they do not have to be accountable to fashion or institutions.

So Where Has the Avant-Garde Gone?

In a recent advertisement, the high-end watch manufacturer Tag Heuer announces itself as ‘Swiss Avant-Garde since 1860’. This inversion of a notion associated with radicalism for the sake of a luxury brand, a corporation allied to high capitalism, is perhaps not as alarming as it first sounds. It is highly symptomatic of how globalization has internalized and absorbed currents of left-liberalism.

In one fell swoop, an idea associated with bohemianism, artistic experimentation, and, with it, penury and misfortune, for the sake of wealth, has become repositioned toward a product that most of us can either not afford or justify buying.

It’s perverse alteration also demonstrates that ‘avant-garde’ has undergone a dramatic metamorphosis since it began to be used in the late nineteenth century. Indeed, that such a company can both sanitise the term of its radical associations while simultaneously profiting from it is but one example of the fact that the avant-garde no longer exists in its historically 'authentic’ form.

In art, it is best used in mainstream media for work that is left-of-field, unintelligible, highly experimental, and uncommercial.

One of the sources of confusion for mainstream audiences with contemporary art is this very absence of a cohesive 'avant-garde' by which the institution and the academy can be dialectically measured. And to the lay audience, this difficulty is exacerbated by a lack of a discernible set of rules or concerns within contemporary art, which seems to have more than several sets of rules, thus making qualitative measurement seem arbitrary or partisan.

These misperceptions are understandable and forgivable. They are, however, not the fault of those without the requisite education or knowledge. Instead, the problem resides in the so-called art world and the little importance given to experimental, not-for-profit galleries and spaces against commercial galleries, who themselves maintain close de facto ties to significant collections and institutions.

Corporations and Art

To go with another commercial analogy: for at least the last two decades, large corporations like Coca-Cola Amatil, Nike, Levis have spent large sums finding out the visual, aural, and structural languages of subcultures.

They do so not only observing from the outside – which is now easier than ever with social networking, which is in many ways a complex system of ad hoc surveillance – and from within, paying members of gangs and social groups (skateboarders, surfers) for information about new words, new gestures and ways of dressing.

This information provides both the framework and the detail for what they design and how they market their products. In other words, the particular languages invented by specific groups are reflected back on these groups for their material exploitation, usually with a swiftness that makes the process invisible.

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that innovation within the cultural sphere occurs according to strategies and within groups that are hostile to commerce. They are not avant-garde in the term's strictly historical sense, but they represent sites of invention and resistance.

This is the same with art, albeit in a slightly more organized way. Artist-run-initiatives – commonly referred to as ARIs – and their more institutionalised offshoots, experimental art spaces are where what we might call the ‘pure’ art happens. The art of process production and discovery whose translation into a commodity is incidental, if not resisted.

Cutting-Edge Art

The passage from radicalism to conservatism, from rags to riches, is a story told across all areas of human endeavour, from politics to art, which also relates to the transition from youthful zeal to stoic old age.

In art, the relationship between experimental, radical, anti-establishmentarianism, and power halls became discernible in modernity.

Experimental art, the art that is defiant of the establishment, is nevertheless tied to money. To target and be hostile to money is also to be bound to it. Experimental, avant-garde, and 'cutting edge' art plays against how art is reduced to a commodity, to something of monetary value. But history has also told us that, by no will of its own (but sometimes also that), art of this kind becomes quickly absorbed onto the capitalist system that reduces all aspects of life to a commodity.

Early or forerunner artists of what eventually call the avant-garde such as Théodore Géricault (1791–1894) and Gustave Courbet (1819– 1877) were inextricably tied to politics. Their appeal to the common cause and freedom was a guarantee that their art was authentic.

Both the artists' masterpieces, Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819) and Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio (1855), were thick socio-political motivations. They were also, notably, exhibited unconventionally.

The exhibition of Courbet’s massive painting, which was for him an allegory of his life and, by extension, the life of painters of his own time, is a story unto itself. In preparation for the 1855 World Fair (part of the cycle of international exhibitions that began with the Great Exhibition in London in 1851) in Paris, the exhibition jury accepted eleven of Courbet’s works, but not that one.

Courbet, who had so much invested in this painting, was incensed and took the decision personally. After all, the painting's subheading was 'an allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life'. Defiant, he enlisted the help of a friend, the art collector Alfred Bruyas, to help set up an independent exhibition called 'The Pavilion of Realism'.

Courbet charged an entry fee. Although entrants were relatively few and appreciators were fewer, Courbet’s example signified that the umbilical cord of patronage had been severed for good and that it was the artist's duty to be independent and to take risks.

His ‘Pavilion of Realism’ became the forerunner of the ‘Salon des Refusés’, the Salon of art that the official Salon had rejected (‘refused’). This would germinate in the Independent Salon that would be so important for the exhibition of the Impressionists.

Footnote: as a testament to the way radical art is absorbed into the halls of tradition, Courbet's Painter’s Studio can now be seen in all its glory at the Musée D'Orsay, Paris, maybe the of the most significant museum for nineteenth-century art.

The Subsequent History of Alternative Venues for Exhibition

The subsequent history of alternative venues for exhibition reveals that they were less dramatically public and more private, intended for the like-minded and sympathetic. This was especially so for the Surrealists, a diverse and fluid group, who staged their semi-formal gatherings.

In other cases, art germinated from relatively modest places. One of the birthplaces of Dada was the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, a small venue where people gathered to witness Hugo Ball sprouting nonsense dressed in outlandish futuristic costumes.

The exhibitions and events staged by the Dada and Surrealist artists showed that art was a living phenomenon in which the final work was to be seen as a punctuation point in a much larger process of not only one artist but of many artists together.

For although modern and postmodern art has undergone considerable mutations, what has not changed is the need for artists to band together with the like-minded for support and growth.

In the past, these associations may have eventuated in a discernible group with its own ‘ism’, whereas today this is not so, although an artist may be named together with his or her anecdotal affiliation with a group of artists, a place, a particular look, tendency or inclination.

This change from a more identifiable set of classificatory boundaries to a cultural environment that is more shapeless, and therefore harder to categorise is not to diminish what occurs in recent and contemporary art practice. But identifiable or not, there is a discernible continuity in experimental and dissenting art practice since the late eighteenth century since ideas are favoured over financial approbation.

The Meaning and Function of Official Venues for Showing Art

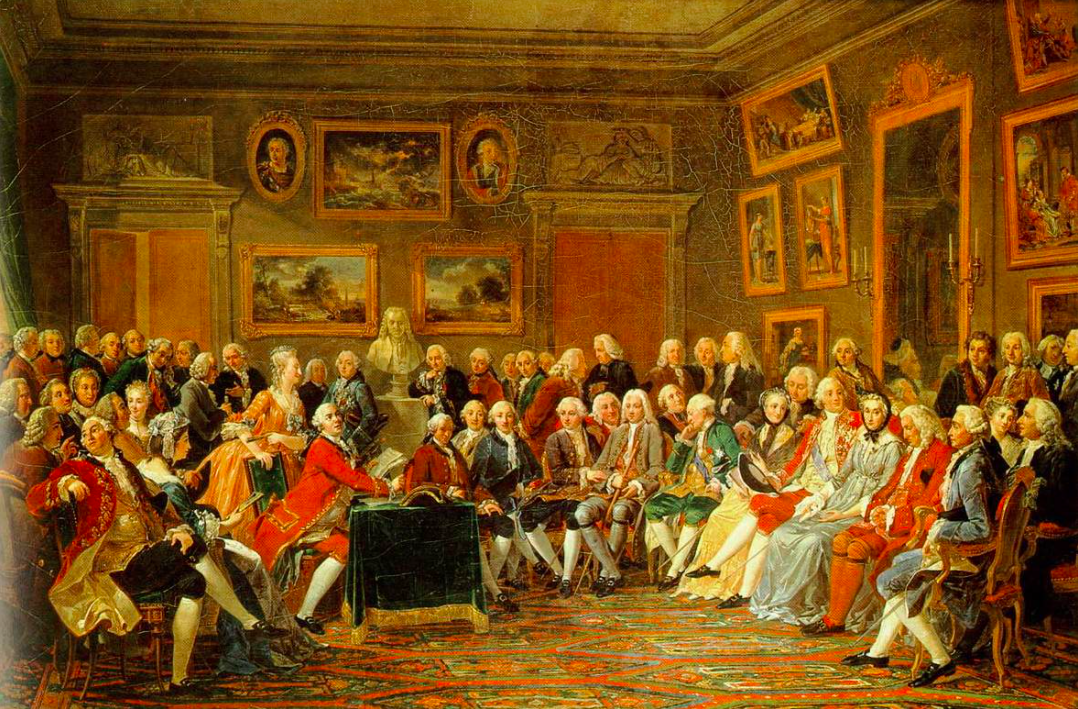

Before discussing venues for ‘avant-garde’, experimental and unconventional art, it is important to reflect back on the meaning and function of the French Salon itself as a bastion of artistic excellence. Spoiler: it was also a bastion of state control.

In 1648, Louis XIV’s chief minister Cardinal Mazarin (1602-61), established the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture, which served as the benchmark for the others that followed: sciences (1666), architecture (1671), and music (1672).

In 1673 the recently founded art academy held its first exhibition, the purpose of which was not just to impart knowledge, but centralization, to be maintained by something resembling objective standards, upheld strenuously by the first of the redoubtable academy’s masters, Charles Le Brun.

By making the artists compete for honours in the annual Salon, by appealing to what Napoleon would later refer to as every man’s love of ‘shining baubles’, the state was more assured of attracting able young artists who then could be assigned public commissions.

Ancient Rome had always fostered the spirit of competition to exert its control over the bureaucracy and the military, but never in the arts. Given that in the arts, egos are worn so close to the sleeve, peer group pressure works wonders and is the mainstay of art's most enduring vulgarization, the competition.

It is worth remembering that the Venice Biennale hands out medals, until the end of the nineteenth century, the Paris Salon was the single most significant event for art. It had the same clout and topicality as any Dokumenta in Kassel or Whitney Biennial in New York.

The role of state power with major art institutions should never be forgotten or undervalued, although these very institutions are at pains to claim their independence. But it is the very assertion of independence and absolute purity of mind that makes state museums' conservatism all the stronger since it is covert and not admitted.

From the Art Gallery of NSW to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the staged exhibitions are facilitated by corporate sponsorship and by what is most likely to attract visitors.

Moreover, the art that is collected in such institution is subject to a vetting process that usually takes account of an artist’s provenance, that is, not only as a certification of authenticity but in the case of contemporary artists, the kinds of private collections that have sought out the artist, and the kinds of venues that have exhibited his or her work.

From the point of view of the public institution, an acquisition or maybe just a showing (where the artist is given an honorarium, the euphemism that dodges the reduction of artistic labour to filthy lucre), the judgment must work backward from the level of official approval an artist has earned.

Because of this, the kinds of works in public collections are by, and large conservative and of a certain order, namely published examples of works exemplifying an artist's career and in a medium that is preferably not perishable.

Installation art and its related ephemera are precarious to stage, hard to preserve and the costs relating to their re-installation and de-installation difficult to justify in relation to hanging a painting. Complex works may be rolled out less often, or they may require support from benefactors and bequests.

On the other hand, the private collections are more likely, to begin with, the work and the artist. Basically, the private collector has no-one to justify and does not need to satisfy a range of criteria, including the pertinence of the newly arrived work with others already in the collection.

While many collectors collect for profit (well they might, since, without such acumen, they would not be in a position to be collectors in the first place), it is the relative indifference to history, dogma, and bureaucracy that tend to make private collections so much more interesting, with all their inconstancies, biases and errors, since so-called errors in judgment can unearth some unforeseen insights.

One prominent example of this in recent memory is the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart set up by a professional gambler, David Walsh.

In both cases, the acquisition and display of works of art are driven by forces well outside the boundaries of what the work of art 'is' and what it sets out to express, communicate, challenge, subvert, or change. The work of art is one factor within the much more forceful vectors of finance and social approval and rubber-stamping.

Dissident Art, the Art of Risk

The birth of dissident art, the art of risk and innovation that questions the social and cultural status quo, can be dated alongside the institution's birth. The word 'institution' requires some qualification here.

Art in the Western/Occidental sense is, in fact, a shorthand for a series of affiliated institutions, which are themselves also discourses, sites of material and abstract exchange.

To begin with, there is the institution that is art as it is understood in broader historical contours: its changing function and appearance; there is the institution of museums and of collecting, and there is the institution of learning.

When we talk about art in the abstract in a philosophical or pseudo-philosophical sense, we usually mean 'good' art as opposed to bad art, which is art only in name or aspiration.

The places where innovation in art has occurred have always maintained an agonistic relationship to learning centres. In the Renaissance, an artist's workshop was a place where artists learned. Simultaneously, the nineteenth and early twentieth century academies now have a notorious connection with perpetuating the styles and approaches approved by the state and its related bodies, museums.

This has changed somewhat when at best, the art school is understood as a place where budding artists can take risks and experiment without, it is hoped, the need to satisfy a potentially paying audience. Since the protest era, we can make a convenient marker of May 1968. Art schools became increasingly the places where the most audacious art was being produced.

Art schools were the Petri dishes for freedom of expression, personal and political. High on the agenda of the art of this age was immateriality: value to the artistic event over the commodity.

In this respect, phenomena that are too often given their separate categories such as Performance Art, Land Art and Conceptualism all shared the same goals. They wished to subvert the gallery space in some way and to remind the audience that the 'truth' of art resides in the kinds of changes and values within the viewer, not according to the monetary or even historical value it may have.

But the most glaring omission in art histories of this period – the period of the age of Aquarius that wished to rejoin contact with nature over commercialised mass culture—is the birth of alternative art spaces. These were not-for-profit venues, now known as ARIs, that were intended as melting-pots for intellectual and artistic exchange amongst artists, writers, would-be curators, and their stauncher groupies.

In a sense, we can say that modern art is defined by the nature of its opposition to the establishment, in a way that would have been anathema in the Renaissance and professional and personal suicide in the seventeenth century.

But with modernism, art became pre-eminently contentious and political. Politics need not have crystallised in the content of the work; it could also be enshrined within a style, hence according to what a work sought to renounce, which in most cases was the academic status quo.

While he was not the first, Courbet's example nurtured the most tenacious binary between the establishment and those outside it. On a much larger scale, the most notorious and famous examples of the alternative scene for art originated in Paris in 1863 with the Salon des Refusés, the venue showing the work not accepted by the official Salon, and now associated with Édouard Manet and the birth of Impressionism, arguably the most popular movement in art of any age at any time.

In many ways, this was a culmination of what had begun around the 1830s when conservatism hit a high point. Charles X, the last of the Bourbon kings and youngest brother of Louis XVI, was deposed in July 1830 after having spent six years trying to reinstitute the monarchy and nobility with the mores of pre-Revolutionary France.

The politicization of art was particularly acute in the 1830s: not only were artists highly galvanized to contemporary events, but major writers such as Hugo and Lamartine assumed important roles in government, the latter playing a significant role in the founding of the Second Republic.

What is highly ironic, though, and another lesser-known fact is that the government-sponsored the Salon des Refusés. Responding to mass protests over the Salon judges' rejection of more than three thousand works, Napoleon III admitted their exhibition, or most of them, in rooms near the main Salon. Ironic or fitting, since it is the inevitable lot of radical politics that it finds itself first defining itself in terms of what it opposes, then ultimately resembling what it once opposed.

The wave of innovation, acceptance, and rebirth that characterizes the avant-garde mirrors the tides of modern politics in its oscillation between Left and Right. It is again one of those curious, disturbing, or consoling historical symmetries that the avant-garde ceases to be pertinent, or to 'be', once the polarities of Left and Right in politics lose their traction.

This radical alteration in the political field is undoubtedly a cause for much anxiety and confusion amongst artists and critics. It is customary to mourn when the easiest thing to do as a member of the Left was to oppose the status quo. However, the 'postmodern turn', the shifts in the contemporary Zeitgeist are aware that such opposition leads no-where in particular.

Left and Right are highly tenuous and fragile designators, and the prospect of perpetual peace, freedom from hunger, and the emancipation of the poor will never be achieved.

Post-Postmodernism?

It is in this vein that Jeffrey Nealon has speculated on this condition, which he calls 'post-postmodernism', which he defines as 'an intensification and mutation within postmodernism (which in term was of course a historical mutation and intensification of certain tendencies within modernism)’.[i]

Regarding the positioning of art and critique in the present age—for which we have used words such as embedded and absorbed—Nealon writes:

Under postmodernism and post-postmodernism, the collapse of the economic and cultural that Adorno sees dimly on the horizon has decisively arrived (cue Baudrillard’s Simulations—where reality isn’t becoming indistinguishable from the movies; it has become indistinguishable) we arrive at that postmodern place where economic production is cultural production and vice versa. And I take that historical and theoretical axiom to be the (largely unmet and continuing) provocation of Jameson's work: if ideology critique depends on a cultural outsider to the dominant economic logistics, where does cultural critique go now that there is no such outside, no dependable measuring stick to celebrate a work's resistance or to denounce its ideological complicity?[ii]

This is a question that many artists, critics, and thinkers outside of this domain are currently grappling with, especially since it calls into question the nature and purpose of innovative art.

Since there is no definable cause or some zone of opposition, then the very task and modality of what one does is called into question.

For at least since the period that this essay describes, since the late eighteenth century to mid-nineteenth century, art had grown into a tool for exploration and explosion, a means by which ideas about life and the world are confirmed or expressed.

In his seminar 'Terror on the Run', the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard describes the masterpieces of modern art (this is not exclusive, but presumably he chooses them for timely relevance) as examples of a terror that, while more striking and visible, have the power to supersede the possibility of a worse terror of mass proportions.[iii]

However, this is quite a big claim to describe milestones of art such as Picasso’s Demoiselles D’Avignon or Beethoven’s last string quartets in terms of terror has the welcome consequence of making one admit that their genesis is entirely unaccountable.

Unexceptional works of art are accountable and still have contact with the prosaic and mundane. According to Lyotard, echoing Nietzsche, great art perpetrates violence on the world; it is a vast cauterization, a spiritual wound. We are surprised, challenged —relocated to a place we might or might not want to be.

Art at its best supplies the jolt that to the surface of complacency and habituation, which exacts violence of social and political proportions when taken to the limit. Note there was no good art that came out of Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, or Maoist China, except those who opposed it.

Visiting Museums

It is also this underlying oppositionism within art of the last few centuries that have tended to make the lay public fundamentally hostile to it. In his still relevant and classic book conducted from research in the 1960s, L’Amour de l’art (The Love of Art: European Museums and their Public), Pierre Bourdieu and his collaborator Alain Darbel conclude that visiting museums is the result of class and schooling.

Public museums are an expression of common citizenry and ownership (the state and everyone owns the works of art within a public museum); however, only a tiny percentage of society avails itself of them.

If this is a problem, which Bourdieu in some sense saw it to be, it has been addressed through the premium given to audience numbers and through marketing campaigns that vaunt and demystify the artist, who is almost always long dead. On the other hand, major festivals of living artists such as the Sydney Biennale appear to use visitation numbers as the leading indicator of its success.

Note here that the culture industry, mass marketing, and mass appeal have quashed critical value in the name of popularity. This is a far more severe state of affairs than many would care to admit, but one symptom has been to destabilize the role of the critic who was once judge and now a mere explicator.

The rise of popularism in public museums and in all quarters of life for that matter turns Bourdieu's thesis on its head, as it were. For now, curators, who are more and more like glorified events managers, are gainsaying the likes and wants of a sector of society that doesn’t know what it likes or wants.

As evidenced by the most recent Biennale of 2012, artists are chosen either as cultural quantities (as reflective of the difference in terms of exoticism or guilt), as celebrities (what has now come to be known as 'brand artists'), as exemplars of a 'good' tendency (for instance artists working in a 'relational mode', that is what involves the audience and audience inclusion is what it is all about), or as entertainers. For decades now, certain artists have been named 'Biennale artists', artists who produce works of art that look and smell like contemporary art but are nonetheless not too hard to comprehend or swallow.

For all of these positions, the British art historian and critic, Julian Stallabrass, coined the term ‘High Art Lite’.[iv] Even though he was referring specifically to the ‘Young British Artists’ (‘YBAs’) that emerged in the 1990s, his notion aptly describes the unfortunate way in which contemporary art has manipulated ideas and appearances to maintain a particular impression or belief in being 'cutting edge' while also satisfying the demands of a greater public, primed on the sharp shock and the one-liner of advertising and mass-market culture.

Suppose one were to transpose Lyotard's 'terror' into Stallabrass’s outlook. In that case, one could say is that the 'terror of art' in contemporary culture has dissimulated itself into a quick fix, into mere cleverness over conscience. Indeed, conscience for many artists, such as the greatest lion of the group, Damian Hirst, is for the sentimental and the gullible.

And with this, we begin to see the social function of art shift into entertainment and, more uncannily, a mirroring of art and mass culture, primarily fashion. We could supplement Stallabrass’s thesis and say that what is occurring in high-end experimental ('conceptual') fashion is superior to a lot of the contemporary art of recent Biennales; either that or contemporary art seems to be aspiring to experimental fashion (which is not necessarily a bad thing) or stage design (which probably is).

Art in Pop-Ups and Unofficial Venues

Hard as it might be, it is well to remember that there was a time when even the ‘YBAs’ were unknown. They exhibited their work in disused warehouses and shop fronts. The people who visited these venues were not the general public.

The ad hoc venues serve the basic function of an artist who wants his or her work to be seen. They are also places where the most fertile experimentation occurs.

The Artist-Run Initiatives that one may find in Sydney or any other major city are to be understood as the radical nexus between the process and invention and its institutional and financial consolidation (some would say sclerosis).

Educational institutions come into play as foundation stones for this kind of activity: people naturally form groups according to taste and aspiration. At their best, art schools encourage extreme (if lawful!) behaviour. The sites and spaces of the art school and the ARI deliver confirm that art is primarily a process.

The finished work of art is but a milestone or punctuation point in art as an activity. Hence the skepticism of many artists to works of art on white walls in air-conditioned rooms. In this regard, debates have resurfaced around the display of Aboriginal art, much of which is critically tied to land, community, and hence the place of its making.

The malaise or simple fact of our political age was exemplified in the Occupy Wall Street movement that occurred primarily in the United States after the 2008 GFC. We can cite innumerable causes since then. It is just that this movement was so internationally widespread. The protestors knew what they were opposing but not in whose name, without a policy or alternative or strategy outside of opposition itself. Its death was imminent, and next, no heroism surrounds it except our respect in their best intentions.

Innovation in art is a better version of this. But unlike protestors, it need not have a beginning or end. Its only justification is that it seeks to innovate and to forestall a greater ‘terror’.

In art, as in other cultural forms such as music and writing, innovation can occur at the most recondite level. It is only understood by a few. The process of permeation has begun until it appears packaged and digested in a museum. Much artistic innovation in art schools and ARIs comes in flawed and strange forms, yet the prescient viewer knows that something is happening, something is still alive.

That is the work of art’s purpose, its politic, and its consolation.

References:

[i] Jeffrey Nealon, Post-Postmodernism, or, the cultural logic of just-in-time capitalism, Stanford: Stanford U.P. 2012, ix.

[ii] Nealon, 176-177

[iii] Jean-François Lyotard, ‘Terror on the Run’, in J-J. Goux and P Wood eds, Terror and Consensus, Stanford: Stanford U.P., 1998

[iv] Julian Stallabrass, High Art Lite, London: Verso 1996, revised and expanded 2006.